Share this

Extracting the value of innovation

by Anna Crona

In our previous articles What is Innovation? and How to drive innovation, we have discussed what innovation is and how we can work practically with driving it, from different points of view. This article complements those two by discussing how we realize the value of our innovation efforts, and how we work with innovation management in order to become successful in our innovation work over time.

Realizing innovation projects

If we accept the definition of innovation saying that innovation is something new that creates value [further discussed in "What is Innovation?"], it is not enough to have a plan for how we develop this new thing and then assume it's value by exploring, testing and learning. We have to spread and exploit what we have developed too, in order for it to reach and create actual value for many people. To achieve this, we need to build viable concepts, anchor them in our customers, our company vision and our colleagues, and start transitioning the innovation concepts to an exploiting mode.

Building a viable concept

Driving an idea towards implementation is of course partly about developing and concretizing it in order to define it in its entirety and make it real. This is however not enough. In order to successfully build and implement an innovation project that creates value, we need to take a set of different perspectives in two different steps into account [further discussed in "Important Innovation Perspectives"]. We need to verify that the concept is relevant to customers who are willing to pay for it. We need to find a market large enough and a business model that allows our revenues to exceed our costs. We need to define the concept we are working with, and build it to make it real. Further, we need to mitigate all large risks and anchor our concept in our company. These are some examples of the things we usually investigate and build when we are driving innovation projects - but this is not enough either. Even if we have all these things in place, our concept is not going to be up-and-running, our customers won’t know where to find us and revenues are not just going to start rolling in. We need a plan for going from the current state (where the concept is not up-and-running) to our desired state (when the concept is up-and-running). This is what we call a Go-to-market plan.

"With a go-to-market plan we avoid standing there nonplussed when we reach the implementation phase."

One part of creating and executing on this go-to-market plan is of course anchoring the project within the organization [further discussed in "Anchor in vision and strategy" and "Anchor in network and organization"]. This is however not enough as it only covers one of the important perspectives of driving innovation - buy-in from the company. We need to start similar activities within the perspectives Customer, Business, Tech and Risk as well. We need to set up a plan for how to reach our customers and motivate them to buy the concept. We need to find a way of entering and growing to the desired size on the market, with a business model that can be put into action from day 1 and then scale. We also need to technically develop and build our concept, and we need to mitigate all great risks along the way. Creating these type of plans, along with defining our concept, makes it possible to adapt our concept to the go-to-market plan early on. Further, it gives us a better idea of how and when we can implement it, and how soon we can start making a profit from this new innovation. With a go-to-market plan we avoid standing there nonplussed when we reach the implementation phase.

Apart from giving us this more realistic idea of how to implement and make profit from new concepts, we can also use the go-to-market plan as a guide for how to prioritize. What features will create the most value in the beginning? Who will be our first customers and which are their most pressing needs? Can we sell a slim version of the concept first and then scale it? How? How can we get our message across on our market? These types of questions help us prioritize and make it possible to release and test smaller versions of the concept early on, verifying it’s value, testing it’s capability and anchoring it in the market.

Anchoring innovation projects

Assuming that innovation projects generally aim at developing something new that creates value for many people [further discussed in "What is Innovation?"], we could also conclude that these innovations need to be anchored in these many people in order to be viewed as successful. For a new and independent organization, possibly a start-up, this means anchoring the innovation with their customers and users. This is of course also true for innovations that are developed within established organizations. However, these projects need to be anchored within said organization as well, as they are dependent on the organization financing them and driving them. For an innovator or intrapreneur, this means getting their time and budget sponsored by a budget owner within the organization, as well as gaining their customers and user’s approval. Further, they need to be able to engage others in the organization to start supporting and believing in the innovation if they are to help developing and realizing it. Failing to do so most often means that the project will be terminated.

Anchor in vision and strategy

When initiating and developing innovation projects, we must take care to anchor them in the company vision and strategy. The reason for this is that we need to make sure that they are relevant to the company aims, and thereby also possible to invest in and budget for [further discussed in "Budgeting and Governance for innovation"]. It does not matter how great an idea or an innovation is if it is not relevant to the company, as the company will never be able to motivate investing time and money in developing and implementing it.

"The sooner we start anchoring, the easier it will be to make sure we don’t spend innovation effort on things that will be rejected later on due to lack of relevance to the company."

This type of anchoring can be done in multiple ways, but the sooner we start, the easier it will be to make sure we don’t spend innovation effort on things that will be rejected later on due to lack of relevance to the company. One way of doing so is adopting “relevance to/buy-in from the company” as one of the parameters we investigate and evaluate the project based on [further discussed in "Important Innovation Perspectives"]. Another way is to start innovation efforts based on the vision and strategic direction of the company (you don’t have to pick either or). Breaking down the company vision and strategy into innovation focus areas or “scopes” helps us find focus for our learning and insighting. That can in turn lead us to discovering relevant problems that the organization wants to solve, and become the basis for our innovation projects. This can be a brilliant way of discovering new innovation opportunities [further discussed in "Vision->Strategy->Scope"], and it helps us keep focusing our ideation and concept creation towards relevant areas.

The way we shape our scopes allows us to target different horizons [further discussed in "Innovation Portfolio and Management"]. This can be done either by stating the horizon we are aiming for, or by shaping and phrasing the scope differently depending on what we are aiming for. Broader scopes allow for wider exploration and a potential to hit horizon 3, while a more narrow scope can limit us more and help us target horizon 1.

This way of working with scopes further allows us to set budgets for scopes without necessarily deciding what the end result will be beforehand [further discussed in "Budgeting and Governance for innovation"]. The scope becomes the basis for the budget decision and helps provide structure to the decision making for innovation. That budget then ensures that resources can be accessed for innovation within this limited focus area. At the same time it establishes a limited area in which we can be creative, without limiting us so much that we don’t have any room left for innovation.

By setting the scope (rather than a set end goal) for our innovation efforts already from the start, we create a frame to learn and develop within, while avoiding to make decisions about what to end up with before we have the information we need to make that decision [further discussed in "Driving projects without a set end goal"]. Having a scope to relate to also helps innovators and contributors to understand and relate to the area that we are aiming to innovate within, and the problem we want to solve, and that provides a good foundation for creativity. Further, the scope can provide a framework for evaluation of projects. Evaluating if a project still fits into the scope is one good parameter to use as an evaluation tool.

Lastly, and maybe most importantly, using scopes help us to make sure that the efforts we put into innovation are put into relevant directions. This can lead to less frustration as we all understand the aim of our efforts, and a better and more impartial evaluation, resulting in that less projects need to be rejected in later stages.

"Without resources and buy-in, innovation projects cannot survive and be implemented and successfully exploited."

Anchoring innovation projects in the company vision and strategy, and in one or several budget owners that can sponsor it is crucial for its success. If the project is not relevant to the company, it should not be invested in and implemented. If the project seems relevant but does not fit into the current vision, maybe we need to rethink our vision [further discussed in "Conditions for innovation within established organizations"]. If there are no budget owners willing to sponsor the project we need to consider it we have not tried hard enough to find them and convince them, or if the company structures and culture does not allow them to sponsor new things. Without resources and buy-in, innovation projects cannot survive and be implemented and successfully exploited.

Anchoring in network and organization

In order for an innovation project to start creating value and fulfilling the demands of being an innovation project - it needs to be spread and exploited. In order to accomplish that, we usually need to transition innovation projects from the explorative phase they start and are developed and concretized within, to an exploiting phase where we realize their value [Further discussed in "Transitioning"]. Making this transition can be a great challenge for companies as these phases or “modes” are substantially different from each other [further discussed in "Innovation VS Operations"]. Further, innovation projects are sometimes handed over to a new project manager at this point, causing new challenges to arise. Anchoring projects in networks and in the organization early on eases these challenges and increase our chances to succeed.

"Making this transition [from an explorative to an exploitative phase] can be a great challenge for companies as these phases or “modes” are substantially different from each other."

Driving innovation projects, that most often lack a clear end goal, is very different from driving a core business project with a predetermined goal [further discussed in "Driving projects without a set end goal"]. This can cause something of a collision when a project is transitioned from one phase to the other. This collision happens between everything from measurements and structures to mind-sets and culture. Hence, transitioning an innovation project to an exploitative phase is a great conversion-challenge that we shall not underestimate if we want to succeed in implementing and exploiting innovation projects.

Further, all innovation projects cannot be transitioned into the existing organization. As the existing organization usually is adapted for delivering today’s value, it is likely to have poor preconditions for taking on projects that aim to create value in new ways and far into the future. This is most likely the case for most horizon 3 projects, hence we need a different approach for exploiting them [further discussed in "Building an Innovation Strategy"].

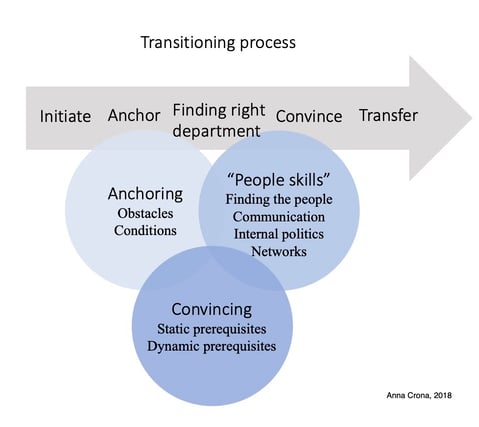

When anchoring innovation projects - before they are supposed to be transitioned - we need to take two dimensions into account. The first concerns practical conditions such as budget, resources, knowledge transfer, project management etc [further discussed in "Conditions for innovation within established organizations"]. The second concerns emotional needs and more “human aspects” [also further discussed in "Conditions for innovation within established organizations"]. In order to successfully transition innovation projects we both need to adapt projects to new project management models and budgeting systems, find the resources required to drive the project and adapt the project to fit the receiver-end. This means that we have to get to know the new conditions that the project is supposed to be exploited within, and making several practical adaptations that are in line both with the exploitative and core business operations-way of structuring work. Further we need to find the resources required to transition the project. We also need to cater for the emotional needs of all parties involved. The receiver and previous project manager need to trust each other, and the receiver must be given the opportunity to understand and become passionate about the project in his/her own way. As the receiver has not been part of the project from the start, this person cannot have the same knowledge and sense of ownership as the previous project manager. All this conversion work needs to taken into account and performed in the transitioning process. Starting this anchoring process early on gives us time to build the relationships and understand the needs of the receiving party. Hence, it helps the transitioning greatly. However, it takes lots of time. Especially since most involved parties will have their full time jobs to take into account simultaneously.

Successfully anchocring innovation projects demonstrably demand some time and effort, and it can be initiated in several different manners. Here follows some examples that can be combined and added to:

- Project managers from innovation projects can be responsible for anchoring their project with a receiver early on. This gives them time to understand each other, and for the innovation project manager to take the receiver's needs into account almost from the start. Trust can be built early on, the knowledge transfer can be started early and the receiver can start building a sense of ownership already in the exploring phase of the innovation project. This can help the receiver be ready, both practically and emotionally, for taking on the project when the time comes. This approach gives the innovation project manager much responsibility for the transitioning early on, as they need to find and convince a receiver.

- By establishing strategic innovation “pillars” in Scopes and Challenges, and asking (and rewarding) people in the core business operations-organization to find innovation projects they can sponsor, take on and exploit, potential receivers can show interest for innovation projects early on, and start following (and potentially financing) them at an early stage. This also allows the receiver to gain knowledge, understanding and a sense of ownership for the project already in the exploration phase. This approach gives all potential receivers much responsibility for finding and taking on innovation projects.

- Combining the two alternatives described above would mean asking innovation project managers to find receivers and potential receivers to find innovation projects. It has the benefit of having both parties engaging equally in this, and could raise the success rate. Both rewarding innovation project managers and core business operations-employees for finding each other seems to be a good way of stimulating transitioning of innovation projects as it both could increase the likelihood of them finding each other, and giving them the incentive to strive for a successful collaboration. What needs to be considered here is that this approach may be best suited for projects in horizon 1 or 2, as projects in horizon 3 may not have a natural receiver in the existing organization [further discussed in "Innovation Portfolio and Management"].

- The management of a company can decide where innovation projects should be exploited by assigning a receiver to each innovation project. The benefit of this approach is that the projects will be anchored in management that can provide a budget to the receiving department from the start, lowering the practical barriers. However, this approach can risk lowering the sense of ownership on the receiver-end if they are not included in the decision making.

- For innovation projects in the third horizon, there is as previously mentioned, usually not a natural receiver within the existing organization. Therefore, we need to assess the options carefully. Should the project start a new department? Should this project be spun out and become a new start-up? No matter how we choose to handle it, we need to take this into account early on in order to prepare the structures and budgets (and maybe also new project managers and employees) necessary to successfully exploit the project.

No matter which alternatives we choose, we need to start anchoring innovation projects as early as possible when we start developing new concepts or business ideas in order to start preparing what is needed in order to successfully exploit them. As an innovation project does not create value and become a true innovation before it has been exploited and provided it’s value to many people, this is one of the key factors in succeeding with one's innovation work.

Transitioning

It does not matter how well we build our innovation system if we cannot implement the innovations we have developed. If we don’t, they will never start creating value, and never become actual innovations [further discussed in "What is Innovation?"].

"Transitioning is the process taking place when a project leaves the phase where we are discovering, building and testing it's “why, what and for who” and we enter a phase where we start executing on the “how”.

Transitioning can be viewed in different ways. One way of defining it is to say that this is the process taking place when a project moves from an exploring phase to an exploiting one - when a project leaves the phase where we are discovering, building and testing it’s “why, what and for who” and we enter a phase where we start executing on the “how”. As previously described in for example [further discussed in “Innovation VS Operations” and “Driving projects without a set end goal”] the mindset and structure of driving projects in these two phases is substantially different, resulting in a potential collision between the two when the transitioning takes place. Tendayi Viki writes in his Forbes article that “The challenge most companies face is that there are very few breakthrough innovations that fit their current structures.” Therefore, companies that wish to successfully exploit their innovation efforts need to spend some time figuring this process out for themselves.

Different transitioning paths

Transitioning can look very different depending on the conditions of the company [further discussed in "Building an Innovation Strategy"] and the properties of the project [further discussed in “Innovation Portfolio and Management”]. An innovation project that is supposed to be transitioned to an already existing department is likely to be somewhat a horizon 1 project, being quite close to the existing business within that department (unless the department is about to make large changes). For a project that is more like a horizon 3 project it may however be impossible to find an internal department that can take on the project within their existing frames. For these projects we need to find new ways within or outside the company. Starting a new department or creating a spin-out (a start-up) are possible alternatives here. There may be many different options when it comes to finding a place that is suitable to transitioning the project to in different organizations, so each innovator and company must consider the possibilities together. The important part is that there are different, previously discussed (to reduce time to decision), options for exploiting innovation projects within the company, that are suited for the different types of projects we choose to aim for.

"The important part is that there are different, previously discussed (to reduce time to decision), options for exploiting innovation projects within the company, that are suited for the different types of projects we choose to aim for."

No matter what type of project we have at our hands, and no matter what strategy for exploitation we choose, we need to start exploring the alternatives and start anchoring the project in the desired place for exploitation early on [further discussed in "Anchoring in Vision and Strategy" and "Anchoring in Network and Organization"]. Anchoring can be made to many different actors within a company. If we have a horizon 1 project at our hands, and want to transition it to an existing department, we start trying to anchor it with a few potential receiving departments. At the same time, we have to try to anchor it with the company vision and a budget owner that is willing to support the project during its exploitation. If we have a horizon 3 project and want to start a new department or company in order to exploit it, we still need to anchor it with the company vision and a budget owner that can support the new entity. This time however, we rather need to anchor the project in people who can become part of this new entity than in people who are part of an already existing department. This could mean starting to “light-recruit” people from inside or outside of the company when the timing is right.

If we persist and have some timing, we hopefully find a department or possibility to start a new entity that could take on the project for exploitation. The next step becomes convincing the budget owners, and others who are supposed to contribute to the exploitation of the innovation, that this is what they should be spending their time and resources on. For an existing department, it may be difficult to take on a project that was not included in their yearly budget and that may not show up on their KPIs as something that will give them credit or benefits. If we are starting a new entity, we have to convince a budget owner (probably further “up” in the organization) that we should spend time and money on building this unit. These are challenges we need time to tackle, and it usually helps greatly if we have built relationships and trust with the people involved beforehand by anchoring the project beforehand.

Lastly, when having found the place for the project to be exploited and convinced some people to invest resources into exploiting it, the big transfer starts. We now have to transfer knowledge, documentation, sense of ownership, relationships and a bunch of other things to the receivers and new owners of the project. This is a process that demands both practical and emotional consideration. We have to fit the project into the new structures and take the dynamics of the exploiting phase into account, while catering for all the emotional needs that can arise then trying to hand over sense of ownership for an innovation project [further discussed in "Conditions for Innovation within Established Organizations - Cultural Prerequisites"].

"We have to fit the project into the new structures and take the dynamics of the exploiting phase into account, while catering for all the emotional needs that can arise then trying to hand over sense of ownership for an innovation project."

The entire process of transitioning demands quite a lot from an innovator or intrapreneur. They need to successfully anchor the project in the company vision and in the people who are supposed to believe in it enough to drive it onwards. They need to convince budget owners and decision makers to trust that this uncertain innovation project is worth investing in. Further, they have to both practically and emotionally hand over an uncertain project that they have driven with passion and stamina, possibly to one or several people who have no previous experience in the exploratory mind-set and way of working. Adding that the innovator him-/herself may have little or no experience from the exploitative phase builds the complexity further. Hence, the people participating in a transitioning, especially the innovator, need to possess much of what we call “people skills” in order to build enough trust with the other party to bridge the differences between the different modes and transition the project in an as good as possible manner.

How can we support the transitioning?

As transitioning of innovation projects is crucial in order to succeed with innovation efforts, and it can be a great challenge for everyone involved - how can we support and ease this process? Well, there are some things a company can establish in order to help. First off, however, we all just need to acknowledge that this process is crucial and that it can be very tricky - hence worth spending some time and effort in.

There are two sets of prerequisites that a company can aim to build in order to ease the transitioning process. The first set contains structural prerequisites, and the second cultural or “more human” ones. The structural prerequisites are the ones we can build more or less static structures around. The concern budgets, incentive programs, KPIs, ways of reporting and other, similar things. The reason these are so important to adapt is because they can easily destroy all chances of a successful transitioning in a second. Tendayi Viki writes in the same Forbes article that “The extent of the needed changes and the willingness of the company leadership to drive that change will ultimately determine the success of innovation. “ A department that has a set budget for the current year, adapted to the exact amount of projects and resources that were planned when the budget was set will not be able to take on another project based on the same budget and resources. There is just no practical possibility. A department that is measured based on their quality and efficiency, and has KPIs measuring how little resources they need to use in order to reach a certain quality/amount of work done is not likely to have any incentives to take on an innovation project. Taking on and exploiting an innovation project means taking on something that is uncertain, complex and certainly not streamlined. Hence, it would make this department would look bad based on their current KPIs - not a very good incentive to become receivers of innovation projects. Therefore, we need to look into our current structures and see if they allow for transitionings at all. If they don’t we need to find ways of starting to allow them. Maybe we can simply add a KPI that measures how many new project departments have taken on and started to exploit, or set aside separate budgets and resources that departments that want to become receivers of innovation projects can make requests from when needed? The same solution won’t fit everywhere, but if we want to succeed with our innovation work, we need to start making room for transitioning.

The softer, more cultural and “human oriented” prerequisites concern everything connected to how people feel and behave connected to transitioning. This stems much from the culture and internal politics of a company, and is of course also partly affected by the structures. When a project is transitioned from an explorative to an exploitative phase, the collision that takes place between the two modes and mind-sets may also take place between the individuals involved. People who normally work with very different things and measure quality and effectiveness in different ways are to come together and unite around a project. This often creates a set of negative feelings and can pose the largest challenge of all when it comes to transitioning [we write more about this in “Conditions for innovation within established organizations - Cultural prerequisites”]. Therefore, transitionings demands that both parties have some understanding for each other, and that they trust each other. Building relationships and networks within the company is therefore a good way of trying to mitigate the negative effects of this collision.

"It has to feel "worth it" for the parties involved in a transitioning to show the grit that is required to succeed"

Transitioning an innovation project will always demand individual grit and that all parties involved take responsibility for making it work due to its complexity and the fact that most organizations are not fully adapted for assisting this process. Therefore, it has to feel "worth it" for the parties involved in a transitioning to show the grit that is required to succeed. To answer the question of what makes it feel worth to put in great efforts at work, we need to look into motivational theories and employee engagement [we discuss this partly in “Conditions for innovation within established organizations - Cultural prerequisites”], and maybe this looks different in different settings. However - either if we reward people by for example giving them credit, personal development, monetary rewards or the opportunity to really make a difference - we need to find a way of making this process feel valuable to each involved individual in order to give them the conditions they need to have the grit to succeed.

Starting to anchor a project in a receiver early on, gives time to build relationships and trust between the parties involved, easing the process by reducing the amount of negative feelings evoked. Combining this with structures and a company culture that allow and promote transitioning, and we have come far in our strive towards becoming successful in our innovation work.

Building continuous innovation and learning

Innovation is not a quickfix. We are not likely to discover our next big innovation by luck or chance, or at our first attempt. Innovation work needs to be long term. It demands new ways of working and new competences that we need to practice in order to master. It takes stamina to provide customers with valuable offers over time. Therefore we need to find our own way of driving innovation, and develop it to suit our competences, aims, ways of working, customer needs and conditions. When it comes to innovation within already established organizations, one size does not fit all - as we all don’t have the same preconditions [further discussed in "Choosing Innovation Strategy"].

Innovation Management

BCG writes “Effective leaders sell the dream: they articulate a vivid image of innovation success. They anchor their compelling ambition to the corporate strategy, with specific targets for growth and value creation. They then formulate the strategy that will deliver value, and they define what kind of innovator the organization wants to be—consistent with the company’s current and future capabilities.” This is true for all work, even if the ways of reaching successful innovation work will differ from our ways to success in other areas [further discussed in "Driving Innovation"]. Driving and developing the overall innovation work of an organization means striving to create the best possible conditions for innovation to thrive, while securing the relevance of the company over time. Hence, we both strive for making it possible to successfully drive each innovation project, and for securing our innovation portfolio over time. Navigating this landscape, and developing the over all innovation efforts within an organization is what we call Innovation Management.

"Driving and developing the overall innovation work of an organization means striving to create the best possible conditions for innovation to thrive, while securing the relevance of the company over time."

Some people say that about 1 in 10 innovation projects and start-ups “survive” and are implemented. Alexander Osterwalder writes “It’s this portfolio of many losers, some mediocre ideas, and maybe 1 or 2 home runs that allows them to explore the next big hit.” This tells us that we need to bet on many horses to win once. By also starting initiatives within several scopes [further discussed in “Vision->Strategy->Scope”], horizons [further discussed in “Innovations Portfolio and Management”] and by using different strategies [further discussed in "Choosing Innovation Strategy"], we give ourselves several different “races” to bet on as well. Strategically planning what races (areas/directions) to bet on, and starting many projects within each gives us a broad portfolio of many different possible “wins”. Combine this with a long term work with establishing the right conditions [further discussed in "Conditions for Innovation within Established Organizations"] for succeeding within each project - and you have built a stable, sustainable innovation capability within your company.

Innovation Management Work

Most companies are used to prioritizing projects based on their value, and use that as a basis for laying budgets and making decisions. As innovation projects are very different from core business operations projects [further discussed in "Innovation VS Operations"], we need to find other strategies for budgeting and making decisions. By constantly overviewing our innovation portfolio and making sure we have enough “races” (directions/areas) and “horses” (projects) going at the same time, we can assess their likelihood to succeed and thereby create a basis for decision making. If we have too few ongoing projects in certain areas, we can make a strategic decision to start more. If we have too little activity in certain areas we can provide more resources. If the risks are too high within a certain area, we can start more projects or push the horizon forward to give ourselves the time and resources to learn more. By categorizing and overviewing our innovation portfolio, we can follow areas and projects and make strategic decisions along the way in order to help them succeed and to prioritize our investments [further discussed in ”Vision->Strategy->Scope”]. This is an important (maybe the main part) of innovation management.

"By categorizing and overviewing our innovation portfolio, we can follow areas and projects and make strategic decisions along the way in order to help them succeed and prioritize our investments. This is an important (maybe the main part) of innovation management."

In order to create an overview of our innovation portfolio that we can actually understand continuously and work with, we can map out our “innovation system” [further discussed in "The Innovation System"]. This is a system built out of all our efforts and based upon our innovation “process”. If we can agree on an innovation system, it helps us to communicate internally about different innovation initiatives' status and needed support, while providing a more viable frame for overviewing our work on a strategic level. Defining one's innovation system can be a process of partly discovering it and partly agreeing on it, but once it is there, it will help everyone gather under the same aims and provide a language for collaboration.

Overviewing the collected innovation efforts of an organization from an innovation system perspective also gives innovation managers the opportunity to follow statistics and find weaknesses/development opportunities within the system. Maybe there is a phase where many projects get stuck? Maybe there is a point of decision making where most projects are terminated? Following our innovation efforts over time gives us the opportunity to find and mitigate these issues. Maybe we can find the reason for projects getting stuck and educate ourselves within this specific issue. Maybe we can see that the reason projects are terminated in a certain phase is because the decision maker does not have enough budget and make adjustments there for the future etc. This is an important part in developing the innovation capability within a company, hence also part of innovation management work.

This overview of the collected innovation work within a company also helps budgeting and decision making as it can somewhat foresee how many projects there will be in certain areas and phases over time. This, together with the statistic understanding of how projects generally develop over time within the company helps us know how much budget we need to set aside for projects within certain areas in the future - even if that money is not tied to specific projects [further discussed in "Budgeting and Governance for Innovation"].

By overviewing, following and developing our innovation work over time, we can build a strong innovation portfolio [further discussed in "Innovation Portfolio and Management"], better conditions for innovation within our company [further discussed in "Conditions for Innovation within Established Organizations"], and a higher innovation capability. Additionally we can become strategic in our innovation efforts, and find a balance between our current core business operations and our innovation work by understanding them both as long term efforts. This manner of thinking and acting allows us to work actively towards becoming relevant and keep our competitive edge over time. This is Innovation Management.

The Innovation System

We sometimes talk about “innovation processes” or “innovation structure”. Now we are going to discuss what we call the entire “innovation system”. If the innovation process is a tool that helps the innovator or intrapreneur to do their job, the innovation system is the tool for the innovation manager. It is a system containing all innovation efforts of a company, sorted out over their innovation processes and structures. Hence the innovation system provides a tool for overviewing our entire innovation work, and seeing how it relates to our aims, how it interrelates and how well it actually works. Just as the sales manager has a CRM-system, an innovation manager can utilize a tool that helps him or her overview the entire innovation system. One tool of this sort is of course Hives.

"If the innovation process is a tool that helps the innovator or intrapreneur to do their job, the innovation system is the tool for the innovation manager."

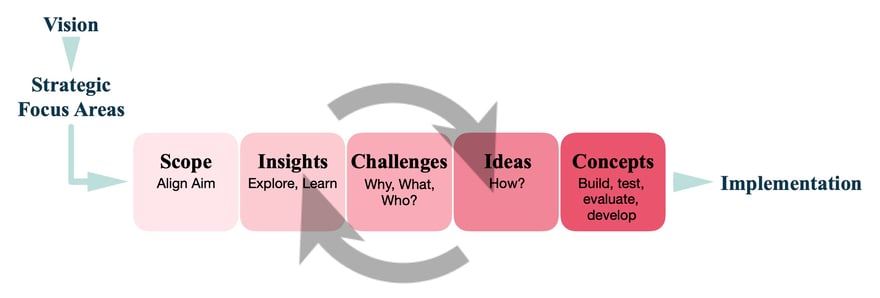

In order to succeed with our innovation efforts, we need to acknowledge that there are different phases to it [further discussed in "The Innovation "Process"]. We iterate our way forward as we (1) Explore, learn and define a problem, (2) Create and evaluate ideas, (3) Build, Test and Learn in order to develop and evaluate the chosen solution and (4) use all learnings to make decisions about the next step. By looping these steps, we move “downwards in abstraction level” and can become more detailed and accurate in our assessments as we learn more. This manner of working is often used to innovate around a specific problem and is usually the basis for an innovation project [further discussed in "Driving projects without a set end goal"]. The same manner of thinking can however be used on an entire system of innovation efforts if we simply move upwards in abstraction level.

Scope: The aim is to define and limit an area we want to explore and drive innovation within.

Insight: The aim is to learn as much as possible within the set scope.

Challenge: The aim is to define a set of sharp challenges, based on the insights, that are concrete enough to be the basis of ideation and problem solving.

Idea: The aim is to create as many ideas as possible, evaluate them and build concepts that solve our challenge and can be further developed to become an innovation project.

Concept: The aim is to develop our concepts and build them into innovations that can be implemented. We loop the process described above ((1) Explore, learn and define a problem, (2) Create and evaluate ideas, (3) Build, Test and Learn in order to develop and evaluate the chosen solution and (4) use all learnings to make decisions about the next step.)

When we reach the concept phase, the innovation project starts becoming something concrete and realizable [further discussed in "The Innovation "Process""]. Before that, we have no idea what result we will end up with [further discussed in "Driving projects without a set end goal"], but we know very well why and for whom. To be clear, this is not a linear process, but rather a very iterative one. We iterate towards a lower abstraction level, not towards a set end result.

By adopting this way of viewing the innovation system (scope, insights, challenges, ideas and concepts) we can categorize and understand the different projects and how they relate to each other and to the bigger vision of the company. Several projects can aim for solving the same challenge and several challenges fit under the same scope. This means that we can have several efforts ongoing in parallel, in order to make sure we develop enough innovations that are in line with our vision and long term aims. As we have no way of predicting which projects and efforts that will succeed, this is a necessary way of ensuring competitiveness [further discussed in "Innovation Management"].

Furthermore, we can start initiatives under a scope that aims towards being implemented within different horizons [further discussed in “Innovation Portfolio and Management”]. Starting projects that aim for horizon 1 and horizon 3 within the same scope in parallel means that we increase our chances of staying relevant both short- and long term. Projects that are in the first horizon will generally end up “later” in the system quite quickly as they usually are in a lower abstraction level and are closer to implementation already from the start. Projects in the third horizon on the other hand, is likely to stay in earlier parts of the system for longer as they start on a higher abstraction level, are more uncertain, and require more exploration and testing before they can be implemented. Distributing the projects over the system and different horizons allows us to overview the needs and state of our different projects, and understand how we can support them. Projects in later phases can be asked for more details, we can dare invest larger in them and work in longer cycles. Projects in earlier phases are less certain and usually need less money and shorter cycles to proceed. Further, this way of working helps us understand how well prepared we are for staying relevant both short- and long term.

Adopting the innovation system view also allows us to gather contributions from people at different stages of the development, helping us to utilize all employee input available. Some people may be more adept at contributing with insights and learnings, while others would rather contribute with ideas and suggestions for solutions. Asking for input at different stages of the system allows us to address different groups of contributors asking for their inpur. The common language helps people understand how they can contribute in a relevant way, and allows for relevant follow-up. Sorting the contributions into the system then helps us make sense of them and utilize them in an effective way.

"Continuity in our innovation work provides the opportunity to both learn and develop our innovation capabilities and become strategic in our innovation efforts. This hugely increases our chances of being successful in our innovation work over time."

Following the scope->insight->challenge->ideas->concepts structure allows us to return to things we have done before and analyze what went good or bad, or go back and bring a terminated project back to life at a time when for example the market is more ready. It also provides us a common platform for collaboration, and helps us stay focused on one phase at the time while iterating our way towards lower levels of abstraction, towards exploitation. Further, and maybe most importantly from an innovation management point of view, it gives us a continuity in our innovation work and provides the opportunity to both learn and develop our innovation capabilities and become strategic in our innovation efforts. This hugely increases our chances of being successful in our innovation work over time.

Share this

- Monday (1)

- Friday (1)

- Sunday (2)

- Friday (4)

- Tuesday (5)

- Saturday (2)

- Thursday (16)

- Monday (18)

- Saturday (9)

- Wednesday (15)

- Wednesday (5)

- Thursday (6)

- Tuesday (1)

- Tuesday (3)

- Tuesday (1)

- Wednesday (3)

- Monday (1)

- Friday (1)

- Sunday (1)

- Saturday (1)

- Sunday (1)

- Friday (1)

- Thursday (1)

- Thursday (1)

- Sunday (1)

- Tuesday (1)

- Saturday (1)

- Thursday (1)