Share this

How to drive innovation

by Anna Crona

In our previous article, we discussed what innovation is, why we need it and why it is so hyped today. This post is more practically oriented! It will discuss How we drive innovation in practice, How leaders of innovators could become successful, How we can view innovation strategy and How companies can work with insighting on a company level. Our goal is to share how we believe innovation work can be carried out. We are also curious about what you think about these matters - please feel free to share your thoughts and experiences at the bottom of the post.

Driving innovation projects

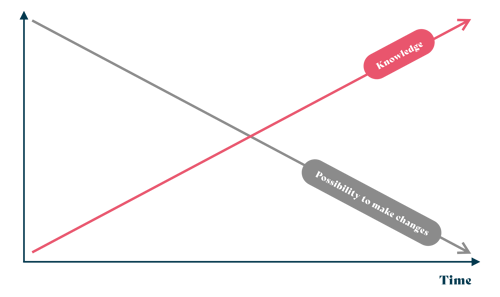

The project manager or the person working closest to an innovation project, not the manager, is always the owner, main driver and success factor of the project. The people working closest to the project are the most knowledgeable and up to date as they are the ones driving and gaining all learnings connected to the project and specific topic.

As innovation concerns something new, there is no previously existing knowledge about specific innovation projects and it is impossible for a manager or someone who is not working in the project to be experts in this specific innovation. Hence, the people driving innovation projects are best suited for making operative decisions for and having ownership of the project [further discussed in The Shift]. They are responsible for any pivots and all development, and for taking the project forward, or terminating it. This way of working demands quite a lot from innovation project leaders and drivers, and implies that managers need to take on a different role. We write more about this in Leading Innovators.

As innovation concerns something new, there is no previous knowledge and no specific area to be expert within.

So what does innovation projects demand from the people responsible for driving them? They need to be able to operate under the great load of uncertainty innovation projects imply [further discussed in Driving projects without a set end goal], and they need to do so willingly while keeping their engagement and motivation over time. They also have to wrestle with the fact that their organization may be poorly adapted for what they are trying to achieve [further discussed in The Shift]. Under this strain, they are to perform the craft of driving innovation. In order to succeed, they need to be able to shift between many competence areas and levels of abstraction (higher level; purpose, problem statement, relevance, terminating or investing in the project, lower level; specific functions and their construction, specific customer needs, detailed business models), while avoiding to fall in love with their project and losing the ability of being objective. As the manager role will no longer be responsible for the progress of the projects, the project manager and owner needs to take on that responsibility themselves. Hence, organizations that wish their innovation initiatives to succeed need to take active measures to support these people, and establish the right conditions for them to do their job [further discussed in Conditions for innovation in established organizations].

Driving projects without a set end goal

The conditions for driving innovation projects are completely different from the ones in action when driving other types of projects. Driving innovation means driving something new and unknown, which is going to create value [further discussed in What is Innovation?]. Core business operations project, on the other hand, usually has a set end goal, which can be broken down into pieces, stacked in “ques” or gantt-charts and used as schedules and delegation charts. The pieces can also be used to evaluate and asure quality at the end of the project [further discussed in Innovation vs Operations].

As there is no chance of predicting the end goal of an innovation project from the start, this “normal” way of structuring work simply does not apply. As opposed to core business operations projects, where the aim is to hit a predetermined goal as efficiently as possible, we aim to (1) define a problem and develop a concept, and (2) decide if we want to proceed investing in the project when driving innovation projects. This is something we need to continuously decide to do - or terminate the project. Either is okay and a natural part of innovating. Therefore, we need to use a more trial-and-error based approach in order to develop and drive innovation projects. This method is way more difficult to plan beforehand and not very useful as an evaluation tool. Instead, we need to work in cycles towards lower levels of abstraction, and acknowledge that we will find ourselves on the wrong path several times, and be okay with changing directions (pivoting). This creates iterations in our work and demands that the ones driving the project dares to and understands when to change directions, or terminate [further discussed in Engagement and Sense of Ownership]. BCG writes “By failing, failing again, and winning, they empower teams to learn through real-world experiments and maximize for outcomes, not output”.

The trial-and-error approach can of course sound like chaos. However, this is not the case. Instead of using our end goal as a guide to development, it is possible to use a problem statement or vision. Evaluating projects and next steps with a problem statement or vision as the base allows us to assess a project's relevance. We can also look at the largest threats to succeeding with implementing the project and assess their likelihood to occur and how difficult they will be to mitigate. As long as the project is relevant to its purpose, and likely to be possible to implement, it can still create value.

Innovation - Structure or Chaos?

Just because the structures we use for core business operation work does not apply for innovation, we don’t have to be completely unstructured. Rather, many statements and methods today indicate that structured innovation efforts are generally more successful than unstructured ones. The key is to find new sets of structures, which are adapted to the properties and conditions of innovation projects. At Hives, we advocate leaning on a framework for innovation, rather than strictly following a rigid structure. A framework helps us to relate both to our own and to other’s work and adapt our way of working and which competences we utilize, depending on where in the framework we are currently working. A framework also enables us to communicate what phase we are currently in, and what type of support and help we need from colleagues, decision makers and customers. This helps us work, collaborate and communicate more effectively. Since the process of driving innovation is iterative and dynamic, structures for innovation need to be as well. Rather than implementing rigid and imperative frames, structures can be used as a tool for improved focus and more effective communication.

Method for innovation

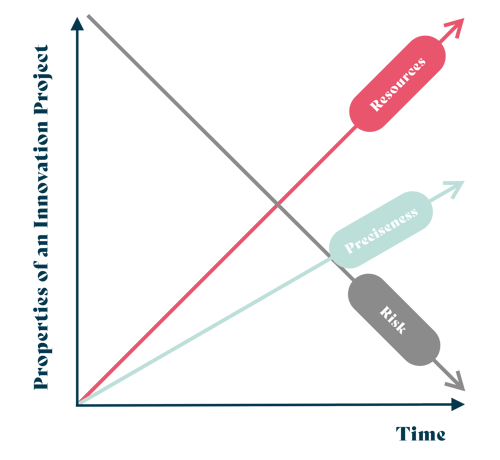

A dynamic framework allows drivers of innovation projects to move freely between the steps or phases, and have different focuses depending on where they are in their work. The goal is always to develop the project and learn how to implement or terminate it. As there is no concrete end goal, and as we learn as we go, we need to start at a high level of abstraction, applying low levels of precision and detail [further discussed in Driving innovation projects]. As we learn more, the project will evolve and our iterations will lead us to lower levels of abstraction, where we have higher precision and more details. The more we learn, the more we lower the risk of investing time and money in the project, and we can access more resources allowing us to dig even deeper and learn even more. This method is the basis for how we work practically with developing innovation projects.

The “more new” something is, the greater the uncertainty, the higher the level of abstraction we need to start at. This is due to the fact that we know less about these projects. Hence, we start in less detail and with smaller investment. Typically, these projects are starting from the third horizon [further discussed in Innovation Portfolio and Management]. Projects in the first horizon usually have more known parameters, and we can therefore start them on lower levels of abstraction, and invest more in precision and resources from the start. This is due to the lower level of uncertainty also implies lower risk.

"The "more new"something is, the greater the uncertainty.."

As the next step of the project is always discovered in the last, and what is right and wrong for the project is continuously discovered by the ones working closest to the project, these people will be the experts in driving their project. This implies that an innovation project manager can never await operative directives from a manager. They themselves know more about the project than their managers, and they therefore need to lead the way and make decisions themselves. This requires the innovation project managers to act less “awaiting” and more progressive, and actively drive their projects themselves. For project managers to be able to act in this way, they need to have permission (both organizational and psychological) from the organization to do so. They also need to have suiting competences and be engaged in the project in order to have the ability and grit required to cope with the uncertainty.

"Driving innovation is a craft. It demands the project managers to shift between mind-sets, competences and levels of abstraction."

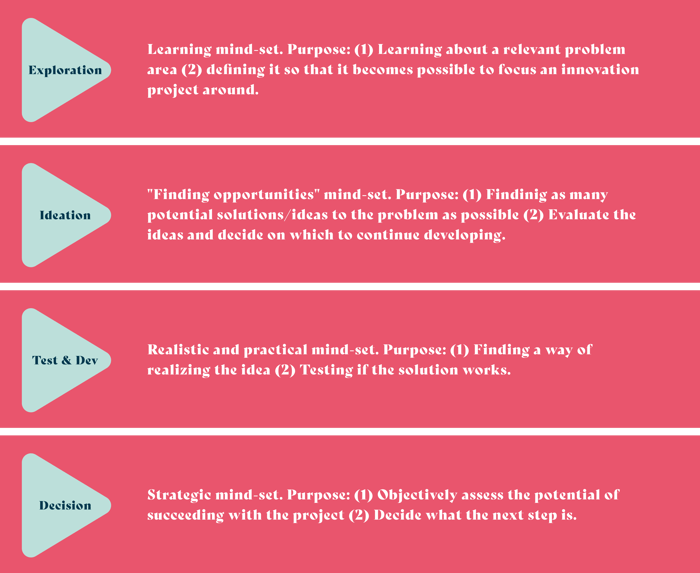

Driving innovation is a craft. It demands the project managers to shift between minds-sets, competences and levels of abstraction. They need to smoothly make the shift between applying a holistic view, discussing e.g purpose, and being detailed and verifying that a specific function can be built. Sometimes, a learning mind-set is required, sometimes the focus is finding new opportunities, and sometimes they need to be realistic and evaluate if a project should be terminated or invested in. This, in combination with the strain of fighting the unadapted organization [further discussed in The Shift], makes driving innovation a motivation-challenge. It can be difficult to get attention and investment from internal actors, and it can be difficult to convince oneself of the value created by the project. Therefore, we must hire people with competences in the craft of driving innovation, give them the opportunity to educate and develop themselves and support them, enabling them to have the energy and will to continue. Doing so can make the difference between succeeding or failing with innovation efforts in established organizations.

The innovation “process”

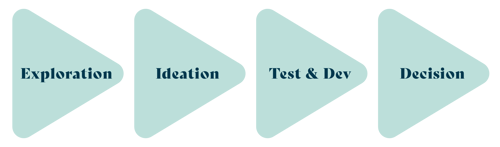

There are many ways of formulating a “process” or framework for innovation. Breaking them down, most of them advocate almost the same way of working.

1. Explore, learn and define a problem

2. Create and evaluate ideas solving the problem

3. Test and develop the chosen solution

4. Use the learnings to decide what the next step is

Shortly, it could be:

As for every other innovation process, these steps are of course iterative and are meant to move back and forth between when developing concepts towards lower levels of abstraction [further discussed in Driving Innovation Projects]. The steps are not meant to be a rigid process, but rather a help to focus and orient oneself to a specific phase and mind-set. Being able to describe what phase the projects are in and what mind-set is needed, also helps collaboration and communication as it helps people align in their efforts. Hence, it helps people working with innovation to “keep track” of their efforts.

The different steps have different purposes and are benefited from using different mind-sets. Agreeing on where we are helps aligning a team’s effort and focus.

In all steps, the different perspectives described in [further discussed in Important Innovation Perspectives] can be used as a help to move forward and keep track of what needs to be developed in order to succeed in implementation or termination. Different tools and methods for e.g ideation and test and development can also be used to move forward in the different steps.

Important innovation perspectives

Using a vision, purpose or problem statement as a guide when driving innovation is very useful, as there is usually no other concrete goal to aim for. We talk about this in Driving Innovation Projects. Except from a problem statement, there are a few more perspectives which are crucial to take into account to make innovation projects succeed. These perspectives can also guide innovation projects as they help us discover the likeness of succeeding with projects, and what “threats” to tackle first.

Innovation can be driven within any area, and start from many different perspectives [further discussed in In what areas can we drive innovation?]. In practical work however, it is important to take more than one perspective into account. These perspectives can be called “Customer”, “Business”, Technology”, “Relevance & Buy-in from the company” and “Risk”. Focusing on these perspectives helps innovators to develop their project in all crucial matters, and decreasing the risk of discovering large risks late on. The process of discovering and developing the project within these areas will of course also be iterative and start in fast cycles using small amounts of resources and precision [further discussed in The Innovation "Process".

The Customer Perspective

The customer perspective is concerned with understanding the user and customer (this is not always the same person/actor). First off, we need to define a relevant target group. This helps us focus on a specific crowd rather than trying to understand all human needs. Looking into the company target group and learning about different customer segment’s needs and wants can give clues to what group to target. When having decided on a target group, we start learning about their relevant needs and underlying drivers. This way of working is also applicable if e.g developing a new way of working internally. Then, the user target group will be the people that are going to work in the new process or structure and the customer the budget owners that will sponsor the project. Another aspect of the customer perspective is verifying that the problem we are solving or the value we are adding is real and relevant to the target group, and if they are willing to pay for it. Lastly, when we have come to the stage when we are trying to find ways of implementing or releasing our innovation to the market, we also need to consider how to reach our customers and increase our customer base over time.

The Business Perspective

The business perspective has two dimensions. One concerns the market, and the other concerns the business model. For the market-part, it is interesting to look into market size and the dynamics of the relevant market. How large market share can we take? Which are the competitors and substitutes? The market perspective also handles the main stakeholders for a project. Who are they and what is their interest in this innovation? Later steps would include looking more into how to enter the market. How are we going to get the market share we are aiming for?

The business model part is of course concerned with finding a viable business model. What type of revenues can we create and what costs will we have? Further, we must look into how we can scale the business model and what implications that will have for shaping the innovation. The second step would be to find ways of getting the business model up and running, and seeing when it will break even. What investment will we need in order to succeed, and how can we get them?

The Technology Perspective

The technology perspective concerns building and realizing the innovation. Is it possible to build what we are creating? How can that be done? Is the technology available? If the innovation is for example a new way of working, this perspective concerns how to implement and realize this new way of working. What impediments are in our way? How can we mitigate them? The technology perspective is also where we consider IP and patent protection. The next step will then be to find a way of going from the current state to the desired one, the one where the innovation is up and running. Do we have the resources and knowledge to make it happen? Here, we also make a concrete plan for building our innovation.

The Relevance and Buy-in-Perspective

The relevance and buy-in-perspective is about anchoring the innovation in the organization and finding potential investors. Here, we take the company vision and strategy into account. Is what we are trying to achieve in line with the greater vision of our company? We also need to find internal ambassadors and sponsors/investors who can anchor the project and invest in it in the future. The earlier this is done, the more likely the project is to gain internal support. Not gaining internal support is likely to mean that the project will eventually be terminated. Including internal stakeholders early on, helps finding an angle for the innovation that internal investors and budget owners find relevant. There is also time to gain their confidence. The second step here is to discuss the implementation with these internal stakeholders and find ways of realizing the innovation.

The Risk Perspective

The risk perspective aims to keep us “sober” when looking at the potential of the project. Finding the greatest risks early on both helps us to focus on the most pressing matters and it enables us to mitigate them and anticipate other’s skepticism. This helps us to get buy-in from stakeholders as well. Further, this perspective helps us realize then to terminate a project. If the risk of not being able to develop a feasible business model is too great, maybe the project is not worth pursuing any longer.

In practice?

There are many perspectives and models you can use to take these perspectives into account. One example is the model Ideo advocate. They discuss “Desirability”, “Viability” and “Feasibility”. It does not really matter what model or method you choose, as the reason for using them is not missing any important perspectives when developing the innovation projects rather than following a best practice.

Many companies miss to include these perspectives in their innovation efforts. One example of this can be starting an innovation department for the “sharpest” tech-people and asking them to innovate. If these people are not complemented with the knowledge about the other perspectives (by education or other colleagues) , they risk developing amazing technology inventions that are not relevant to any market or customer. Thereby they don’t innovate at all (they are inventing), as the things they develop never start creating value for people [further discussed in What is Innovation?], and the effort will never succeed. The same goes, of course, for the other perspectives. This dynamic creates a need for mixing competences and asking people with different knowledge to collaborate and contribute with their input to innovation.

Leading Innovators

The “old school” production companies were organized in silos and each silo was responsible for making sure they delivered on their part [further discussed in The Shift]. Today, if we want to work with innovation, we need to think differently. Being a good manager for innovators is different from managing people working in other domains [further discussed in Innovation vs Operations]. It is much more about being an enabler and supporter, than delegating, controlling and following up on decisions. Today’s innovative organizations need to be built for networking and collaboration, and we need to be able to work with abstract things, without a concrete end goal. We need to shift our perception of who is creating value in a company, and apply new ways of managing and leading our organizations. McKinsey writes: “To make a corporate culture friendlier to innovation, managers must acquire new skills to engage and lead the staff.”

As the experts in driving specific innovation projects are the ones working closest to the project [further discussed in Driving Innovation projects], managers can no longer break down and delegate tasks. They just don’t know more about the daily operations and progression of the projects than their employees anymore, the tables have turned. This makes the manager who gives order and practices control obsolete. Instead, managers need to become leaders and start coaching, networking and coordinating. Managers are often also budget owners. This implies that they are responsible for communicating the general innovation direction and making investment decisions that are needed in order to move forward with innovation [further discussed in Conditions for innovation within established organizations].

"Managers just don't know more about the progression of the projects anymore. The tables have turned."

To coach innovators, leaders and managers need to hand over the “sense of ownership” to innovators and project managers. They need to trust their employees to drive the projects forward, rather than await orders. If managers step in and start running the projects, they risk damaging the innovator’s sense of ownership. Jeffrey Baumgarther, for example, writes that managers should not take ownership and start micro-manage the projects. The managers role becomes more about asking coaching questions that helps the innovators to find their own path to success. To become accomplished at this, managers must adopt a “coaching approach”. Tuff ledarskapsträning, for example, describes this as (1) relating to the potential of the employee, (2) letting the responsibility for the project rest with the employee, (3) circling in and clarifying the goal, (4) letting their own agenda go, (5) “Sitting back” and allows the employee to find his or her own way and (6) caring about the employee and their goal.

Having a common language for innovation also facilitates good leadership. This language can consist of processes, words, structures for decision making etc [further discussed in several parts of this post and in The Definitive Guide to Innovation]. The language helps the manager and employee to reach a common understanding around the projects phase, potential, need for support and what should be the next step. The manager does not have to be the expert in innovation (that may be a waste of competence). He or she needs to have expertise in leadership and enough understanding for innovation to be able to ask coaching questions and make financial decisions. Asking the innovation expert to be the manager of innovators would maybe go well together with the traditional way of hiring managers, but managers for innovators will benefit more from their ability to lead and communicate effectively. Having the innovation expert becoming the manager may even become an obstacle, as the risk of micro-managing and damaging the sense of ownership increases.

Making investment decisions is an important part of a manager’s job [further discussed in Decision making and budgeting when there is no concrete end goal]. That type of decision helps innovators to move forward with their projects. Stalling or pushing investment decisions forward may risk preventing progress and, worst case, make the innovators lose momentum and motivation. If possible, the manager gives the innovator the investment. If not, they ask coaching questions aiming to help the innovators build a stronger case. If the manager thinks that the project should be terminated, they can be humble with the fact that they do not have the most knowledge regarding the project, sit back and let the innovators reach that decision themselves - if the project really should be terminated. Acting in this way, and making investment decisions for uncertain projects can feel scary. There is never as much information as there would be in a core business operations project, and therefore the risks are higher than decision makers may be used to. Organizations need to adopt a culture that allows “mistakes and fails” and celebrates the attempt rather than blames the decision maker (or the innovator for that matter) when a project is terminated. The managers need to dare to take risks, or all innovation projects will get stuck at decision level.

Managers for innovators can create great value for their employees by knowing and communicating the organizational structure, and the company's vision and future goals. Access to this type of knowledge enables innovators to network and find relevant sponsors and ambassadors. This gives the innovators access to knowledge from different perspectives and a greater chance of finding an investor for the project. These types of networks can increase the chance of success for innovation projects, writes McKinsey. Managers can also take on the role of ambassador or sponsor themselves, and their support can contribute to legitimacy for the innovation projects. A manager who openly supports and invests in an innovation project is a great ambassador and provides lots of value when the project is going to be anchored internally. Robert Tucker describes this in his Forbes-article. Managers for innovators can also assist when it comes to finding relevant directions for innovation projects. By ensuring that the projects are relevant to the company, they help the innovators succeed. BCG writes: “Leading innovators empower cross-functional teams with shared goals to discover and pursue customer-centered growth opportunities—and then work in sprints to create, launch, and learn from minimum viable products (MVPs) in the real world.”

Adopting this type of leadership may match current processes and delegation structures poorly. In the production society, the manager was supposed to be knowledgeable, have control and be able to report results upwards in the organization. Many managers do still today have rigid budgets that are supposed to generate a set ROI. Stuck in these structures, creating good conditions for horizon 3 projects can feel impossible. McKinsey found that “Only 28 percent of the senior executives in the survey said that they are more likely to focus on the risks of innovation than on the opportunities, but only 38 percent said that they actively learn from innovation failures and encourage the organization to do so as well. Even more alarmingly, only 23 percent of the employees believe that their organizations encourage them to learn from failure.” This shows the result of the difficulty managers can be stuck in in traditional organizations, and what it implies for innovation work. How are people supposed to know the ROI of a project they cannot even predict the next months work for [further discussed in Innovation Portfolio and Management] and are not the experts in? This indicates that we need other ways of creating budgets and doing governance when managing innovation projects [further discussed in Decision making and budgeting then there is no concrete and goal].

Decision making and budgeting

- when there is no concrete end goal

The fact that innovation projects do not have the same type of concrete end goals as other types of projects [further discussed in Driving Innovation Projects], makes it almost impossible to use the same methods for budgeting and decision making as we normally use for core business operations projects. As the end goal is unknown, it is not possible to use the end goal as a benchmark for quality or right and wrong, or set a rigid budget for the entire project from the start. Further, the experts and people who know the most about the innovation project are not the people who are usually responsible for decision making [further discussed in Leading Innovators]. These conditions force us to think differently about decision making and budgeting.

As innovation projects usually start at a high level of abstraction, with few accessible details, we cannot use detailed information to make decisions. This implies that investing largely in innovation projects early on in the process is a risky business. At the same time we have to make decisions in order to move forward and develop the project. Having to make decisions to move forward and accessing more detailed information that can become the basis for the decision that we cannot make until we have the more detailed information puts us in a “Catch-22 situation”.

"Having to make decisions to move forward and accessing more detailed information that can become the basis for the decision that we cannot make until we have the more detailed information puts us in a Catch-22 situation"

One way of solving this conflict is utilizing “affordable loss principle” - we just don’t invest more than we are willing to lose. Smaller investments early on allows the innovators to continue working, developing the project and getting the information required to make larger investments. An affordable loss budget can be kept dynamic and we can use it to invest wherever we see fit. The higher the level of abstraction and the less details, the lower the investment. Investing a little at the time is one way of dealing with the uncertainty of innovation and avoiding becoming paralized.

The more developed and concrete a project gets, the more we know, the smaller the risk of investing. Thereby, we can increase the investments gradually. This way of working is well aligned with the methodology described in [further discussed in Driving Innovation Projects]. That section discusses how innovators can work their way down to lower levels of abstraction by iterating their way forward and utilizing more resources to learn more and be more detailed. In the same way that innovators can utilize different perspectives when developing their projects, decision makers can utilize the same perspectives to assess if a project is worth investing in or not [further discussed in Important Innovation Perspectives].

This way of working is not that common in established organizations with a legacy from the production society [further discussed in The Shift]. It can be hard for a manager to implement these methods and ways of thinking without buy-in from top management. Therefore, we recommend managers to discuss this method for budgeting and decision making with their top managers early on, in order to align expectations and find suitable structures for this type of method. Doing so gives top management a chance to adapt their way of thinking, working and budgeting as well (or at least choose actively not to). We write more about how we can handle budgeting and governance on a strategic level in [further discussed in Budgeting and Governance for innovation from a strategic point of view].

Conditions for innovation within established organizations

As innovation work differs so much from core business operations work [further discussed in Innovation vs Operations], it also requires completely different conditions. Due to the large difference between the two, it might be easy to draw the conclusion that innovation needs the opposite of the structured, optimized and controlled processes that have become so successful for core business operations work. If so, the optimal condition for innovation would be chaos. However, this is not the case. Innovation work demands structure to become successful, just not the same structures as core business related work.

"Innovation work needs structure, just not the same structure as core business related work."

McKinsey writes “There are no best-practice solutions to seed and cultivate innovation. The structures and processes that many leaders reflexively use to encourage it are important, we find, but not sufficient. On the contrary, senior executives almost unanimously—94 percent—say that people and corporate culture are the most important drivers of innovation.” BCG also writes that: “...even large tech companies such as Amazon and Google that are known for their innovative cultures use a guiding structure of governance and process. Both companies encourage risk taking, but they also have stringent capital controls, resource-allocation mechanisms, and clear processes in place to guide projects or kill them.” This section will discuss a few categories of conditions that are fundamental for succeeding with innovation work in an established organization.

The shift from production society to knowledge society moves the highest level of knowledge and value creation from the “top” of the organization, to the “bottom” [further discussed in The Shift]. The value in the knowledge driven organization is created through constant learning and transfer of learning into projects that can realize the value. Management becomes a support function whose main task is to establish the right conditions and meet the prerequisites for the value creating learning and development driven by the employees. Hence, both management and employees get new roles in the knowledge society.

Structural prerequisites for innovation

The first order of business for a company who aims at becoming innovative is deciding to go for it. Becoming innovative comes with commitments to financial, structural, cultural and competence investments. Deciding to become innovative also means accepting and acknowledging the difference between innovation and core business operations [further discussed in Innovation vs Operations], and starting to build the conditions required for innovation to flourish. McKinsey, for example, writes that if a company wants to succeed in their innovation efforts, they have to integrate innovation into their strategic agenda. Not being ready to commit forces organizations to question if they really want to become innovative.

The structural and practical prerequisites for innovation are the ones we can fulfill by building structures and taking practical actions. We cannot use the structures we have in place for core business operations, but we still need structure in order to relate to our work and to collaborate. Structures are needed to find ways of distributing resources, time, competence and budgets. They also offer help in finding ways of evaluating and implementing innovation projects. Lacking structures risks putting innovation projects in a vacuum as they will not fit into any existing structure, meaning that no one will know how to handle them and give them what they need to succeed. Hence, we build structures to ensure that innovation projects get the resources and conditions they need to flourish.

When building structures for innovation, we use the conditions they need as a foundation for our structures. Examples of such foundations are making sure the projects can access budget, resources and competences [further discussed in Decision making and Budgeting when there is no concrete end goal]. If there is no budget for innovation, no one will have time to work with innovation, and nothing will be done. If there is no time for innovation, maybe due to full back-logs, there will be no innovation. Are we lacking relevant competences and knowledge, there will be no innovation. And so on..

Having established the conditions for innovation, we also need to make sure innovation projects can access them. If there is no ability to make decisions regarding investments in innovation projects, having established a budget for innovation will not help, as it cannot be distributed to the ones needing it. Even though making decisions for innovation projects is different from making other types of decisions, they still need to be made. Therefore, organizations wishing to successfully drive innovation needs to find ways of utilizing the basis’ for decision they can access and utilize them as a foundation for how to make investment decisions [further discussed in Decision making and Budgeting for when there is no concrete end goal and Budgeting and Governance for innovation from a strategic point of view].

It is not enough to be able to drive innovation projects within the organization to become an innovative company. The initiatives need to be implemented to reach and create value for many people, and become “real” innovations [further discussed in What is Innovation?]. If there is no practical possibility for existing departments to take on and implement innovation initiatives, and it is not possible to start new departments or companies who can implement innovation initiatives, they will never survive long enough to start creating value. Hence, organizations must be prepared to implement innovations. Being prepared means having a plan for how to move resources from current activities to start implementing innovation when that is needed. It can also mean having resources that can help starting new departments or companies when that is required. Further, there needs to be decision makers who can make this type of decisions, and budgets that can finance the transition of innovation projects into implementation. It may be very difficult to know what type of implementation that is suitable for specific innovation projects beforehand. However, it is always possible to be prepared for and have access to the different alternatives in general. It is also possible to implement different ways for innovators and implementers to find each other within the company.

Strategic direction

Making sure innovation work is relevant to the company in which it is driven is crucial. All innovation work therefore needs to be in line with the long term goals and vision of the company. Otherwise, it becomes difficult to motivate investments in the initiatives [further discussed in Vision->Strategi->Scope]. There are however more reasons why strategic direction is important for innovation work.

Having a strategic direction for innovation work provides a relevant purpose that can act as a foundation and a frame that helps all creative work by establishing a sense of meaning. This helps people access their creativity and is a good source of motivation, which is a crucial ingredient in innovation work [further discussed in Driving innovation projects]. Further, having a sense of meaning and purpose helps people strive in the same direction. Not having people strive in the same direction, writes BCG, might lead to all innovations becoming incremental and difficult to scale.

The strategic direction for innovation can be manifested in different manners and exist on different levels of abstraction. The crucial part is that it allows and stimulates innovation. The first step towards achieving this is shaping the company vision to aid innovators. This can be done by looking into how the vision is formulated. An innovation-enabling vision is narrow enough to provide a frame or purpose, but wide enough to allow different types of innovation. A vision that for example mentions today’s core product will make it very difficult to motivate initiatives aiming to develop new products, or even start delivering services. A vision that is vaguely formulated or too open will however provide very little guidance for both innovators and decision makers and risk paralyzing them. Therefore, formulating a vision is a balance between providing a frame and hindering. Further, we must remember that a vision is of no help unless it is well known by the employees and anchored within the organization.

The strategic direction for innovation can also stem from so-called scopes [further discussed in Vision->Strategi->Scope] or challenges. These statements are strategic directions on lower levels of abstraction that describe challenges/problems or values the company wants to solve for or provide their customers with. Breaking down strategic directions and making them more concrete provides an evaluation guide as well as a potential creative motor on lower levels of abstraction.

Lastly, strategic directions can be used not only as a guide for innovators, but as a guide for decision makers as well. Investment decisions in innovation need to be evaluated on several parameters, and relevance to the company is one of them. If there is a well formulated vision, scope and challenge, it becomes easier for budget owners and decision makers to evaluate if a project is in line with the company aims, and if it should be invested in or not.

Cultural prerequisites

It has been said that culture eats strategy for breakfast. If that is true, it implies that fulfilling the cultural prerequisites for innovation is a crucial necessity for achieving successful innovation. The HBR-article "Proof that positive work cultures are more productive" by Emma Seppälä and Kim Cameron describes the general importance of a positive culture. Below, we are discussing some specific points that are relevant to innovation work.

Trust

In organizations that have a non-trusting environment, innovation efforts are likely to struggle. If employees don’t trust their managers and trust that their contributions are viewed as valid and will be utilized, they are not likely to to contribute and dare make their own decisions. If managers don’t trust that employees are able to bring out the next business model or core value offer, or make any decisions for themselves, they are not likely to allow and value their employees' opinions and contributions. If employees don’t trust each other, they are not likely to collaborate or accept transitioning of innovation from one team to another. If managers don’t trust each other, they cannot collaborate and open doors for their employees to achieve networks within the organization. Further, when people don’t trust each other, there needs to be solid control systems in place to ensure progress and quality. These control systems also hinder innovation. Hence, we need a trusting culture to succeed with innovation.

McKinsey writes that “Topping the list [of mindsets and cultures that promote innovation], in our research, were openness to new ideas and a willingness to experiment and take risks. In an innovative culture, employees know that their ideas are valued and believe that it is safe to express and act on those ideas and to learn from failure. /../ There is also widespread agreement about the cultural attributes that inhibit innovation: a bureaucratic, hierarchical, and fearful environment. Such cultures often starve innovation of resources and use incentives intended to promote short-term performance and an intolerance of failure.“ This statement underlines that openness, willingness experiment and to contribute to innovation and other aspects crucial to succeed in innovation, stems from a trusting culture.

One important term to discuss on the topic of trusting organizations is psychological safety. Laura Delizonna writes in her HBR-article that Paul Santagata [Head of industry at Google 2017] “knows the results of the tech giant’s massive two-year study on team performance, which revealed that the highest-performing teams have one thing in common: psychological safety, the belief that you won’t be punished when you make a mistake.” - and it makes sense, right? If we want people to contribute, make their own decisions and drive innovation forward themselves, without acting “awaiting” we must establish psychological safety. Otherwise, we risk missing out on all this due to the fact that our employees are too afraid to take action. Delizonna continues writing that “Barbara Fredrickson at the University of North Carolina has found that positive emotions like trust, curiosity, confidence, and inspiration broaden the mind and help us build psychological, social, and physical resources. We become more open-minded, resilient, motivated, and persistent when we feel safe. Humor increases, as does solution-finding and divergent thinking — the cognitive process underlying creativity”. These characteristics seem to be a good foundation for succeeding with innovation. Delizonna further describes how to achieve psychological safety in her article “High-Performing Teams Need Psychological Safety. Here’s How to Create It”.

If we are going to establish cultures that enable and enhance innovation, we need for example to allow and value a trial and error based approach and keep a mindset saying that failure is learning. We need to openly value everyone's contribution and make sure to show and give credit for the result, practice as we preach, let employees in on important decisions and be transparent and actively choose to trust each other, starting with top management. This list is of course not complete, and there are several more things that can be done in order to achieve a trusting and enabling culture. As a basis, we need to think about what the people driving innovation need in order to succeed and what hinders we can remove to enable them to work effectively. This is the opposite of shaping cultures and structures in order to create a system that enables management to control and enforce. Here, we start with the employees instead.

There are a bunch of other measures to take if aiming to establish a culture that enhances innovation, and many of them are tied to structures [further discussed in Structural Prerequisites for Innovation]. If we cannot shape our structures to fit innovation, we don’t lead by example and a trusting environment will be very difficult to achieve.

Transparency

To achieve successful innovation, there needs to be transparency in the organization. Transparency is crucial, both for enabling employees to make decisions and contribute with relevant knowledge and ideas [further discussed in The Shift], and for people to be able to collaborate. An employee who knows the strategic direction of the company and is aware of what is going on internally and externally will be well prepared for making decisions, contributing and collaborating. An employee who only knows his or her part of the organization and value offer has no fair chance of contributing in a relevant way as they don’t have the knowledge required to create and assess ideas/opinions.

"An employee who knows the strategic direction and situation of the company is well prepared for making decisions, contributing and collaborating."

To achieve transparency, we must make information accessible for every employee. Accessible means that the information is available in a manner where everyone can absorb it. Hence, it must exist in any language (national or occupational) spoken within the company, be formulated in a way that people with any background can understand and make sense of. It also needs to be available in channels people are actually consuming. It is not enough to publish a vague or academic vision or report on the Intranet and call it transparency.

Types of information that can be relevant to be transparent about:

- Vision and strategy of the company

- Innovation challenges/problems

- Information regarding the progress of different initiatives

- Information about the current company status

- Collaboration opportunities and potential partnerships

Transparency is crucial in order to enable employees to contribute and make relevant decisions. However, it also has a part to play in establishing engagement. Asking employees for their input and informing them that their contributions were valued, developed and utilized is a good way of showing them that they are valued, in action, which could also evoke and/or keep engagement. Further, knowing that what you are contributing with has a meaningful impact on something you can relate to and know about can provide a sense of meaning for the individual, which is a crucial ingredient in establishing motivation.

Engagement and Sense of ownership

As driving innovation can be tough and demanding [further discussed in Driving projects without a set end goal], motivation and engagement is crucial for success. If the person driving innovation is not motivated, he or she is not very likely to have the stamina to take on the challenges of driving these types of projects. Respondents in a McKinsey survey of 600 executives and managers indicated that trust and engagement were the mind-sets most closely correlated with a strong performance on innovation.

There are many ways of enabling engagement among employees (here is one article discussing this topic). Examples below:

- Set up goals [further discussed in Vision->Strategi->Scope]

- Show appreciation and that contributions are valued [further discussed in Transparency]

- Make sure there is time for learning and development for employees [further discussed in Learning Culture]

- Show faith and trust. Stay away from micro-management [further discussed in Leading Innovators]

- Let project managers and innovators keep Sense of Ownership [further discussed below]

Having the sense of ownership (a psychological ownership) for one’s project can be a great source of engagement and motivation. Robert Bullock writes about how “Motivating Employees Has Everything To Do With Giving Them Feelings Of Ownership” in his Forbes article. Having a sense of ownership can for example mean being allowed and able to make decisions regarding the development of one’s project, and knowing that one possesses the ability, mandate and resources to realize or terminate a project. As the people most knowledgeable about innovation projects are the ones driving them [further discussed in The Shift], enabling a sense of ownership by implementing these conditions seems reasonable - both from a structural and cultural perspective. Asking managers who don’t have the same amount of knowledge to make all decisions for an innovation project can lock the development, as they don’t have the knowledge (or drive) to make these operative decisions (budget decisions may still need to be made by managers who know about the entire budget). Getting stuck due to lack of decision making may lead to that the innovation project loses momentum and the innovator loses his or her motivation. This may decrease engagement and, worst case, evoke a feeling of hopelessness.

When it comes to budget decisions, there is sometimes a good reason for leaving them to the managers or budget owners who can have an overview of all initiatives they need to invest in and coordinate investments across the organization [further discussed in Innovation Portfolio and Management]. The investment decisions can come from the managers or budget owners, but the foundations for the decisions still need to come from the innovators [further discussed in Leading Innovators].

To keep the sense of ownership at the innovators or project managers, leaders and managers (and others) need to stay out of the way and not “steal” this psychological ownership. This is a trap that is easy to fall into when having a legacy from the production society. In the production society [further discussed in The Shift], the managers were responsible for making sure that the employees were delivering on their targets. Here, the manager is responsible for enabling innovation and development of projects and employees instead - not for micro-managing the projects. This for example means that the manager is not allowed to start making operative decisions. He or she must also let innovators or project managers present and promote their project themselves as the owners of the projects. A manager who, for example, starts presenting innovation projects to higher management as their own risks taking away the sense of ownership from the project manager/innovator.

"Here, managers are responsible for enabling innovation and development - not for micro-management."

Being an engaged innovator, there is one risk or bias you need to take into account. Spending so much time and energy on a project, you risk falling in love with your project and become biased towards keeping it running. This means that you risk driving the project further than necessary in a certain direction or resist terminating it for too long. Therefore, innovators always need to try to stay objective and remember that you sometimes need to “kill your darlings”. One way of avoiding this may be to “fall in love” with the problem or purpose, rather than the ideas and solutions. The organizational culture can also help by not blaming people who terminate problems, but rather celebrate the learnings the project led to.

“Learning culture”

An organization that aims at being innovative needs to have a “learning culture” - a culture that stimulates and enables learning and explorative behaviour. “The single biggest driver of business impact is the strength of an organization’s learning culture,” says Josh Bersin, principal and founder of Bersin by Deloitte. A learning culture can be defined as “a culture that supports an open mindset, an independent quest for knowledge, and shared learning directed toward the mission and goals of the organization” (CEB).

"Asking an innovation project to set a concrete end goal from the start forces the innovators to guess and decide what to end up with before any learning has been done."

Innovation work is dependent on constant learning, as learning is the foundation for development of innovation projects [further discussed in Driving projects without a set end goal]. Employees need to be able to apply a trial-and-error based approach without having managers demanding them to have all the answers from the start. Asking an innovation project to have the concrete end goal all figured out from the start, forces the innovator to guess and decide on what to end up with before any learning has been done.

Working with innovation in this manner means missing many crucial learnings and investing in projects that are based on very little relevant input. Hence, the projects become misaimed and blunt, and are likely to create very little value in the end. Therefore, we need to adapt all measurements, budgeting and structures, as well as our culture, in order to allow a learning environment and culture that enables people to develop projects that do not have a predefined end goal.

Being a learning organization also means viewing terminated projects and initiatives as leaninings. Therefore, these organizations never blame a person who has terminated a project. Instead, they value the learning. Further, being a learning organization means that it must be possible for employees to dedicate their time to seeking and gaining knowledge. There also needs to be a practical way of storing and keeping the learnings in the company. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic and Josh Bersin, for example, write more about how to achieve a learning culture in their HBR-article “4 Ways to Create a Learning Culture on Your Team”.

Negative emotions

As working with innovation is connected to so much uncertainty, there is always a risk that negative emotions will occur. Examples of negative emotions can be stress, fright, uncertainty or demotivation.

Transitioning

One situation which may evoke negative emotion is transitioning. Transitioning of innovation projects from an innovative/explorative phase to implementation in core business operations means shifting from one set of conditions to another [further discussed in Innovation vs Operations]. The people working with the project need to shift their mindset from an explorative one, where the end goal is unknown and structures and measurements are relatively dynamic, to a mindset of rigid structures, measurements and quality assurance, and a set end goal. A person who is used to working with innovation is likely to have different opinions on how to drive projects than people who usually work with core business operations. This may result in a disagreement regarding how projects should be run, implemented and assessed.

The disagreement can concern e.g how to view risk, or what method to use when developing the project. An innovation project is likely to be more risky, contain less detail and be less concrete than the projects people at the core business operations-end are used to. The projects are probably not fitted for the existing structures and regular workflow either. Further, the measurements and targets that are usually set up for core business related operative work are probably not suited for the innovation project. This can create high degrees of uncertainty for the ones that are supposed to take on and implement an innovation project. Further, the general KPIs for the implementing department may not be favouring implementing innovation projects. All these clashes can evoke negative feelings between the parties. Accepting and working on an uncertain project which is not aligned with the currently used measurements is probably less appealing than continuing to invest in the current business, which has already proven to be profitable.

In addition to this, there is a phenomenon called the “Not-invented-here-syndrome” (Seán Kenehan writes about it here) which describes the unconscious reluctance a person or group can feel towards something they have not started, run and been passionate about themselves. The people who are to take on and implement an innovation project have just not been part of the project from the start and have therefore missed the learning and the emotional strive it has taken to bring the project to the point of implementation. They therefore lack both the logical and emotional belief in the success of the project.

The differences between innovative/explorative and operative/exploiting ways of working and mindsets, along with the risk of evoking negative emotions among the parties makes transitioning and implementing innovation projects difficult. Furthermore, there is research indicating that people experiencing negative emotions have a decreased cognitive ability. Andreas Komninos writes about How emotions impact cognition. These perspectives make the transition of innovation projects a very complex situation which has to be tackled to succeed with implementing innovation projects.

"Research indicates that people experiencing negative emotions have decreased cognitive ability."

To ease the transition, a healthy culture of cooperation needs to be established in the organization. Further, it is possible to ease collaboration and communication by starting to anchor innovation projects within the organization at an early stage. Giving the parties time to build relationships and including the implementing party as early as possible can bridge some of the differences, reduce the conflicts between people of different mindsets and help the parties collaborate better in the transitioning.

Fear of becoming obsolete

There is another dimension to negative emotions connected to driving and implementing innovation in established organizations. In [further discussed in Innovation cannibalize on our business], we write about how innovation initiatives may need to be financed by the current core business. Further we discuss that there is even a risk that the innovation outcompetes the current core business. As the people working with and directing the current core business have built their knowledge and position around the current business, this too risks evoking negative emotions. Implementing innovative projects that may make them or their knowledge and position obsolete can make these people feel threatened and scared. This fear is a strong incentive to start opposing innovation.

As innovation projects and -initiatives are dependent on people who are passionate about them, and on being firmly anchored in an organisation that supports and sponsors them, negative emotions can be devastating. Therefore, organizations that aim at becoming innovative have to establish a culture that enables and expects employees to develop and increase their competence over time. They also need to create conditions for successful implementation of innovation, with as little negative emotions as possible.

Collaboration

Let’s assume that we need to cover all innovation perspectives [further discussed in Important Innovation Perspectives], and that the experts within these areas are located at the far extent of the silos of the organization [further discussed in The Shift], or even outside of the organization. The natural conclusion is then that we have to collaborate over the silos to succeed. PWC writes that “Innovative companies aren’t going it alone. Instead, they’re pushing the boundaries of innovation both inside and outside their organizations by breaking down traditional barriers, tapping a much wider ecosystem for ideas, insights, talent, and technology, and incorporating the customer throughout the innovation process.“A BCG survey from 2017 also found open collaboration to be a significant factor separating the best from the rest, the best reported to be supporting open collaboration 77% of the time, compared to just 23% for the not so strong performers.

In order to be able to collaborate, employees first of all need to know who to turn to to find collaboration within a certain area. Then, they need to be able to reach out to each other. Further, they need to have time and a space to get to know each other and build relationships. In order for them to be able to do that, the governance methods of the organization must allow and encourage collaboration. In an organization where no one knows anyone, except from within their own silo, and the governance methods don’t encourage employees to deliver anything outside what has been delegated to them from top management, it will be very difficult to collaborate across silos or competence areas. Adding a culture which implies that the silo who delivers the best on what has been delegated to them is the best one, we risk creating a culture where people don’t want to share their knowledge and don’t want to collaborate as they risk losing credit from the top management.

Today, we know that collaboration is important, and we have access to many different collaborative tools and methods. However, many organizations are still struggling to utilize collaboration as a means for innovation. Therefore, we need to start both by establishing structures and culture that allows and enhances collaboration, and by implementing tools that help us keep track of the huge network of people we can collaborate with and that facilitate the collaboration. Or, as PWC puts it: “Collaboration is more than technological tools. It’s more than a cultural willingness to work together to come up with new ideas. You need both. And when you combine them, you unlock tremendous power. Now is the time to start turning that key.”

Incentives

Incentives or reward systems have been part of organizational systems for a long time. There are many different ways of designing them, and they all aim at the same thing - getting people to do what the management wants them to do, right?

What are we rewarding?

A traditional way of incentivising employees has been to hand out a reward to employees who achieved the desired results. However, innovation projects have unknown end results [further discussed in Driving Innovation Projects] and require a trial and error based approach. This makes it very difficult to decide beforehand what desired outcomes to reward. Further, it is very difficult to predict which innovation efforts that will succeed and which ones will be terminated. This means that an employee who wants to be sure of gaining the reward would be ill advised to go for driving innovation. Daniel Pink discusses what he called "if-then rewards", meaning that the reward is based on that if you do X you will get Y. In his talk "Driving Employee Engagement", he explains why if-then rewards are great for simple and short-term tasks, but not so good for complex and long-term ones. Hence, if we want people to engage in innovation activities, we should find other triggers for motivational rewards.

Some companies arrange “fail festivals” and try to create a culture that celebrates failure in order to get their employees to dare engage in innovation. Henry Doss writes about a few more different possible rewards in his Forbes article “Five Ways Incentives Kill Innovation”. Daniel Pink discusses the importance of Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose in "Driving employee engagement". Another option here could be to reward desired behaviours instead of results. In that way, employees engaging in innovation efforts could be rewarded no matter that the outcome of the projects were, stimulating the start of many more projects and increasing the chance of having a few successful ones. Daniel Pink discusses the importance of Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose.

What rewards are we using?

A traditional type of reward has been money. Organizations have rewarded desired results with monetary compensations packed into for example annual bonuses. Lisa Bodell describes two other possible rewards (experiences and recognition) in her article “3 Non-Basic Ways for Incentivising Employees to Innovate”, and writes that we always have to adapt our rewards to fit our company aims and culture. It is easy to conclude that the larger and more exciting the reward is, the better the employees will perform. Oliver Baumann and Nils Stieglitz don’t agree. They write in their HBR article that “..our research shows that high-powered rewards are no better than low-powered incentives at producing radical innovations”. They may generate excitement and high hopes, but they result in few breakthrough concepts”. They further describe allowing employees to use some of their time for innovation, or staging innovation competitions as possible alternative rewards. These rewards are closer to only enabling innovation efforts and giving people the possibility to participate and contribute, rather than giving employees something they can enjoy in their spare time.

Innovation projects require motivation

Innovation projects are best driven by people who feel a sense of ownership for their projects, and who are genuinely engaged in their problem statement. Therefore, in order to succeed with innovation efforts, we need to strive for creating conditions for people to get into a state of motivation and engagement. There are different theories on how motivation is created. Some believe that we can evoke motivation in others, and some think that motivation can come only from within each individual, but that it is perfectly possible to destroy someone else’s motivation.

No matter what motivational theory we believe in, we need to establish conditions that enable and promote innovation to succeed. This could mean setting aside time for employees to innovate, showing them that their contributions are valued and utilized (recognition), and giving them the mandate they need to make their own decisions and take projects forward. We may also need to establish conditions that allow employees to learn and develop their competence in order to stay relevant and find new opportunities. If these things can be viewed as rewards or incentives, the incentive system will build itself as we are establishing the conditions needed for innovation to flourish. If these conditions are required in order for employees to succeed in innovation, not establishing them risks preventing them from driving innovation and may evoke hopelessness. If we believe that motivation can be destroyed, this may be a very good way of destroying motivation for innovation.

In conclusion, large monetary rewards for achieving desired outcomes may not be the best incentive or reward system for innovation. Believing that people can motivate themselves if enabled to drive development and innovation, and recognizing their innovative behaviours may be a better way to go. Further, each company must find their way adapting their incentives to suit their aims and employees.

Building an innovation strategy

Building an innovation strategy could be defined as: “Taking a holistic approach to finding a way of staying competitive over time”. It comes down to (1) how to structure and create conditions for innovation initiatives to flourish and be implemented, (2) how to budget and govern innovation initiatives and (3) how to formulate long term strategic direction for innovation. Or, as Gary P. Pisano puts it in his HBR article: “A strategy is nothing more than a commitment to a set of coherent, mutually reinforcing policies or behaviors aimed at achieving a specific competitive goal”. Just like in any other strategy-work, the reason for doing it is to make sure everyone strives in the same direction, that we achieve our goals and that our efforts become relevant over time.

What is different about innovation strategy is really only that the conditions and prerequisites for innovation are different from the ones in action related to other types of work. As we cannot really predict the concrete end goal on innovation work [further discussed in Innovation vs Operations], we need to create strategies in a different way than for projects with a known end goal. Further, we must make room for innovation- and core business operations efforts to exist simultaneously within the organization, in order to be viable and profitable both now and in the future.

Choosing innovation strategy

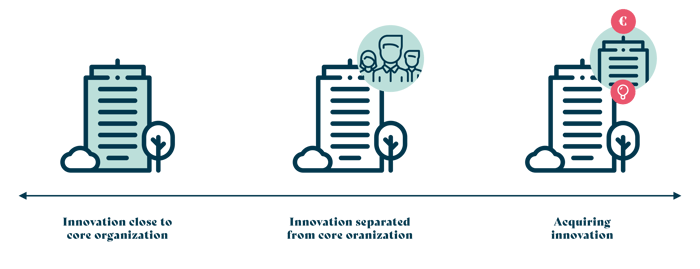

There are different ways of thinking strategically about innovation. We can define what areas to drive innovation within [further discussed in In which areas can we drive innovation?], how we will budget for innovation [further discussed in Budgeting and governance for innovation from a strategic point of view] or how to achieve innovation in practice. This section will discuss innovation strategy in terms of how companies can choose to achieve innovation within their organizations. In this sense, we could say that innovation strategy here is about deciding how closely we want to weave innovation and core business operations together, or if we want to engage in all types of innovation work at the same time. It is important to think about how well the innovation strategy we chose will suit the goals we have set up. If uncertain about where to start - just start somewhere and test something.

"Just start.. Trust that you will find your way by testing and learning!"

Trust that you will find your way by testing and learning, in the same trial-and-error based approach as we apply in practical innovation projects [further discussed on Driving projects without a set end goal]. Starting and testing is the best way of initiating that learning.

Integrating innovation in everyone’s work

It is possible to place the innovation efforts of an organization very close to the current work. This is done by for example asking all employees to spend some of their time innovating. The advantage of this approach is that it includes everyone and invites everyone to contribute. The challenge may be that the people who normally focus on developing today’s core business have the current value offer top of mind and are likely to contribute with ideas and thoughts that relate to that offer and their daily work. Therefore, it might be difficult to achieve innovation in the third horizon using this strategy [further discussed in Innovation Portfolio och Management]. However, it may provide a lot of value in the first horizon. To succeed with this type of initiatives companies have to, except from fulfilling the conditions and prerequisites needed [further discussed in Conditions for innovation within established organizations], and make sure the employees have time and room in their thoughts for innovation. Further, they need to reach out with the message that everyone's input is valued. People cannot innovate if they are troubled by extensive back-logs with short deadlines, or if they are afraid of being laughed at or not taken seriously when suggesting new things.

Using an “innovation unit”

Another alternative is to concentrate innovation work to a specific unit separated from today’s core business. The company can locate and hire people with competence within relevant areas and give them the right conditions to succeed with innovation outside of the existing organization. The advantages with this is that there is no need for a full re-organization, and the employees of the innovation unit are usually not limited by their focus on today’s core business. Further, employees here can spend time doing the insighting work required to increase the “innovation height” and get closer to the third horizon. The challenge may be that these people can lack knowledge and understanding for what is going on in the rest of the organization. This may make it more difficult for them to anchor the projects and get the buy-in that enables implementation. Hence, starting the anchoring early on becomes extra important for these units.

Adopting this kind of unit allows the core business operations to continue as usual, and the unit to focus on innovation. This requires the company and management to be able to "hold two thought or mindsets at the same time". They have to become an ambidextrous organization. The HBR-article ‘The Ambidextrous Organizations' describe the concept with the same name, and talk about allowing innovation/exploration and core business operations to coexist within organizations.

External innovation

A third strategy for achieving innovation is to find external collaborations or acquire start-ups who have already developed relevant value offers. This can be done for example by hiring a group that works specifically with locating interesting partnerships and potential acquisitions, or by working with open innovation. The advantage with this strategy is that it requires less internal resources, as companies can choose to invest only when they assess the risk to be low enough and they will therefore not have to engage as much in early phases of innovation themselves. The challenge can be that merging partnerships or acquisitions into the existing company can be very difficult. Small, new companies are often run by very motivated people and in a very different manner than large, established companies. Having been acquired and given up their ownership, the motivated founders may lose motivation or quit. There is also a risk of the large company suffocating the small with processes and structures that just were not needed when they were a small company. This risks destroying the dynamic, which was probably a key success factor of the small company, lowering it’s value. In partnerships and acquisitions, companies must also consider what brand to use. What brand will the customers like and trust the most? These challenges must be met if this innovation strategy is to succeed.

Practical ways of developing and implementing innovation

Common for all these strategies is that there must be a plan for what should happen when an initiative is ready for implementation. Different innovation projects will need different implementation plans. Some can be absorbed by an existing department, some requires a new department and some needs to become spin-puts and continue as a new company. It is usually not possible to plan this for specific projects. However, companies must be prepared to transition projects from innovation/exploration phases to core business operations phases. Otherwise, projects risk never reaching the market and never start producing actual value. This needs to be considered in budgeting and resources planning, and there needs to be practical ways available for implementation.

Using all three strategies?

It is possible to utilize all strategies at once. They are likely to fill different parts of the innovation portfolio and thereby give the company the opportunity to create value both shortterm and longterm. Choosing all strategis still implies that the practical and cultural prerequisites for innovation must be in place [further discussed in Conditions for innovation within established organizations], and projects started in all strategic areas must have the chance of fulfilling some part of the company’s innovation goals. An organization that for example only aims at being innovative in the first horizon may be wise to use the strategy where innovation and core business operations are weaved together, while ones aiming for horizon 3 innovation should maybe use an innovation unit.

Budgeting and governance for innovation

- from a strategic point of view

Budgeting for a project that does not have a concrete end goal can seem impossible [further discussed in Driving projects without a set end goal]. How are we supposed to do a cost breakdown and set a reasonable budget for a project when we have no idea what needs to be done or what revenue we will have? How are we supposed to know all the costs and revenues for a project with no concrete end goal? No, we have to use a different method for budgeting. One possible solution is to use the “affordable loss” principle. This means setting a budget for how much money we can afford to “lose” if the projects invested in are terminated. It is still important to remember and acknowledge that (1) terminated projects also create value as they result in learning and (2) not innovating will probably result in the largest loss of all, as not innovating largely increases the risk of becoming obsolete.

If we want to drive innovation and competitive edge over time, we need to make sure that the conditions we create for innovation span over several years as well. Anchoring initiatives in vision and long term strategy is one way of ensuring this. Using the vision and strategy as a foundation for the strategic innovation direction within the company helps us ensure that the innovation efforts carried out are relevant for the company [further discussed in Vision -> Strategi -> Scope] (i alla fall från ett företagsperspektiv, [further discussed in Important Innovation Perspectives]). By tying budgets to these strategic directions or scopes, we can create dynamic budgets that span over several years rather than setting static budgets for specific projects. Combining these types of budgets with an overview of the current innovation portfolio helps us understand how we need to budget for innovation and implementation of innovation projects over the coming years [further discussed in Innovation Portfolio and Management]. This also allows us to tie certain budgets to specific phases of projects or invest more money in specific scopes than in others. When specific projects then reach a phase where they need investment, they can turn to the budget set aside for their phase and scope rather than trying to vouch for future revenues they cannot confirm.